by Brad Wright

Fall bull sale season is in full swing and makes this a good time for a refresher course in utilizing EPDs to help you pick your next bulls. For many of you, this will be pretty redundant to things you have heard and read in the past, but it sure doesn’t hurt to make sure you are using the best breeding predictor available correctly.

What is an EPD? EPD stands for Expected Progeny Difference. An EPD is a value that represents an animal’s genetic breeding value for a given trait. As the name implies, an EPD estimates the difference between the averages of 2 animals’ progeny for any given trait due to the genetic differences in the 2 animals. An EPD is a comprehensive statistical tool that combines actual performance and contemporary group data with pedigree data, related animal data, and in some breeds, DNA markers. An EPD is the best predictor of breeding value available to us and should be used for selection over actual data of any animal.

How is an EPD used? In defining EPD, the word “difference†was used several times. This word is key to understanding how to use an EPD. An EPD is a means of comparison to evaluate the difference between an animal and either a) another animal or b) breed average. To calculate a difference, you must have two values. I bring this up only to drive the point that a set of EPDs on an animal with no other knowledge is useless. An EPD cannot be used by itself and it does NOT relate to any value of actual performance (i.e. a BW EPD of 1.8 does NOT mean the calves will be 75 lbs). An EPD can only be used to estimate the difference of the average of two animals’ progeny. When you hear someone say something about “good†EPDs or “bad†EPDs on an animal, they are generally comparing to breed average. Breed average can be found on most breed association websites or printed in most sale catalogs. The important thing to remember about Breed Averages is they are most often NOT ZERO. This one simple fact has disappointed many unknowing producers when the realized their +15 WW bull was actually 9 lbs below breed average for WW (IBBA – Average WW 24). Also, EPDs are calculated within breeds and cannot be compared across different breeds.

BULL A

WW EPD – 24

BULL B

WW EPD – 34

Based on the above information, we would expect the average weaning weight of the calves sired by BULL B to be 10 lbs greater (34-24=10) than the average weaning weight of the calves sired by BULL A, given the same environment and comparable genetic makeup of the dams.

What do you need to help your herd? Back on this discussion of “good†and “bad†EPDs, this cannot be based solely on the bulls ranking within the breed, and will not be the same for every breeder. Know your herd and know your environment and utilize the EPDs to best fit your needs to reach your end product goals. A “good†Milk EPD for a producer in Northern Georgia with 50 inches of annual rainfall may be ABOVE +20. A “good†Milk EPD for a producer in Southern Arizona with 6 inches of annual rainfall may be BELOW +11. Even though EPDs are represented with + and – and percentile rankings, doesn’t mean that + is good and – is bad, and 5th percentile isn’t necessarily better than 50th percentile if it doesn’t fit your herd, your environment and your end product goals.

How accurate is an EPD? Ever wondered what that little number was printed below and EPD? The accuracy of an EPD, sometimes labeled ACC, is often times printed below the EPD. The accuracy will be a number between 0 and 1 and is the statistical representation of the confidence in the EPD. The closer the accuracy is to 1, the more reliable the EPD is and the less likely the EPD will move or shift. Accuracy increases as progeny are recorded. A common problem when buying bulls is that most will be unproven bulls with a large percentage having never sired a calf. This does add a degree of difficulty when evaluating young bulls. With non-parent bulls, the highest accuracies available will be .25 to .35 and these accuracies will only be available on bulls with data collected in large, high quality contemporary groups with at least some proven AI sires represented in the group. This magnifies the need to buy bulls from breeders who are diligent in collecting and reporting proper data and contemporary groups.

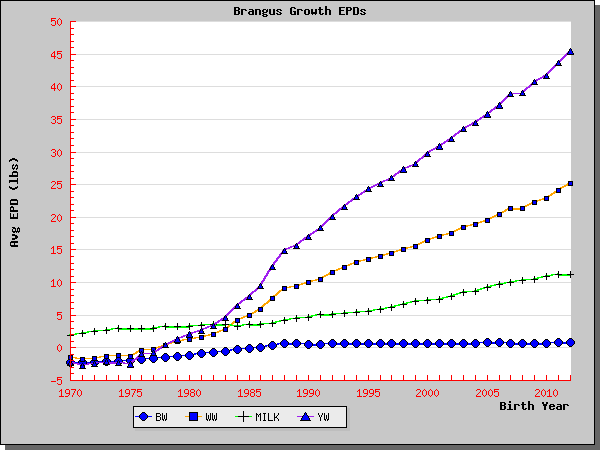

Do EPDs work? Figure 1 shows the genetic trend for the growth traits in the Brangus breed since 1970.

These trend lines are similar to those found in other breeds as well.

With the use of EPDs, breeders have been able to increase Weaning Weight and Yearling Weight while keeping Birth Weight essentially the same. EPDs do work when used appropriately. They can even work too well if only selecting for one trait. There will be constant updates to the EPD analysis in the future, whether it is the addition of DNA data to increase the accuracy of these unproven animals, or the creation of new EPDs to help producers better select for economically important traits like fertility, age of puberty or feed efficiency; but quality progeny data will always be the backbone of EPDs because “proof is in the pudding†(or in the cattle industry, “proof is in the progenyâ€).